Almost a year ago, Prime Minister Kishida promised to have up to 17 nuclear reactors operating at the start of the summer of 2023. The premier’s comments raised much excitement/concern (depending on one’s stance on nuclear power), but all agreed this was a significant acceleration of the restart program. After all, 17 units is just over half of Japan’s total.

It is now the start of the summer, 2023. There are nine reactors online. That number has yet to actually hit double-figures since the nation’s nuclear plants were idled after the 2011 Fukushima accident. And, the two more Kansai Electric units that were certain to swirl into action this and next month are now back “under review” by the regulator with no restart date announced.

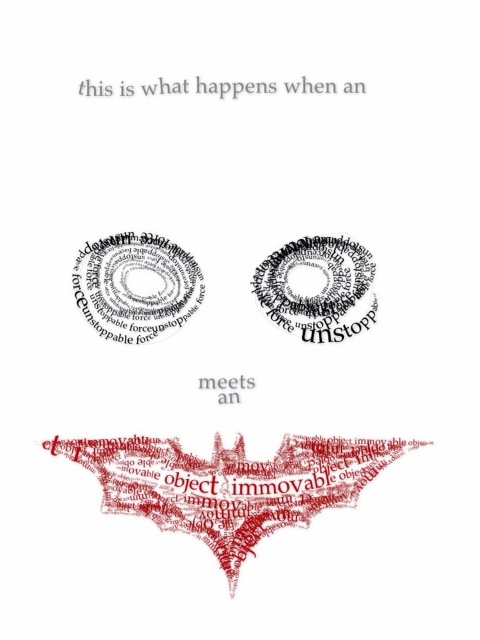

The situation is probably best described as what happens when the seemingly unstoppable force of energy policy, driven by record fuel and electricity prices, meets the immovable object of industry regulation. In the 10 years since its inception, Japan’s Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA) has become one of the most powerful state entities, skillfully rebuffing nearly all attempts by industry and government to wrest control.

Perhaps unintentionally, the NRA now challenges the ability of bureaucrats and politicians to fully determine national energy policy. As a new debate heats up in Japan over policing of the broader electricity sector (see the first article in this week’s Analysis section), the NRA could serve as a useful case study. After a series of recent scandals involving major utilities, the power industry is ripe for stronger regulation. But, will the government accept less policy control?